Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF strongly recommend initiating breastfeeding within one hour of birth for optimal infant health, nutrition, development and growth. This evidence-based recommendation is globally recognized and is a key component of the Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) and the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding outlined by WHO and UNICEF.

In India, this recommendation is officially embraced and actively promoted through multiple national programs and professional guidelines:

- The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare supports early initiation through the Mothers’ Absolute Affection (MAA) program, which is a comprehensive breastfeeding support initiative designed to raise awareness, train healthcare providers, and improve breastfeeding rates including early initiation.

- The Ministry of Women and Child Development includes the same recommendation in the national guidelines on infant and young child feeding, emphasising timely initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth as a critical practice for improving infant health outcomes.

- Professional bodies such as the the Indian Academy of Pediatrics and the National Neonatology Forum of India (NNF) and civil society organisations like Breastfeeding Promotion Network of India (BPNI) have issued clear, evidence-based guidelines emphasizing that breastfeeding should begin as soon as possible after birth, preferably within the first hour to ensure that baby receives colostrum, and to enhance breastfeeding success in the immediate and long term.

Despite well-established recommendations for the early initiation of breastfeeding, many mothers in India continue to face significant challenges in practicing it. This write-up examines the importance of the Early Initiation of Breastfeeding, underlying barriers to practice it and outlines actionable solutions to improve the situation.

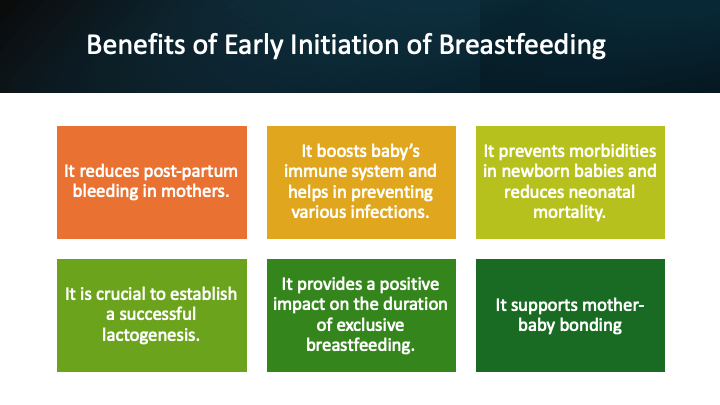

Why is Early Initiation of Breastfeeding Important?

While benefits of breastfeeding in general are well documented, Early Initiation of Breastfeeding (EIB) imparts special health benefits to both, the mother and the baby.

What is the status of early initiation of breastfeeding in India?

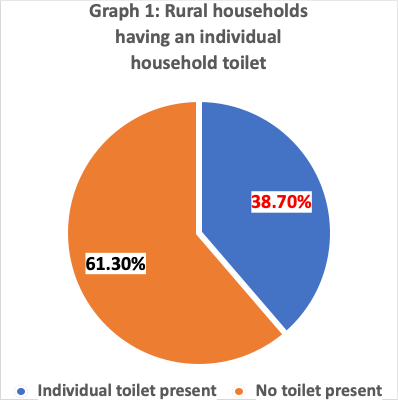

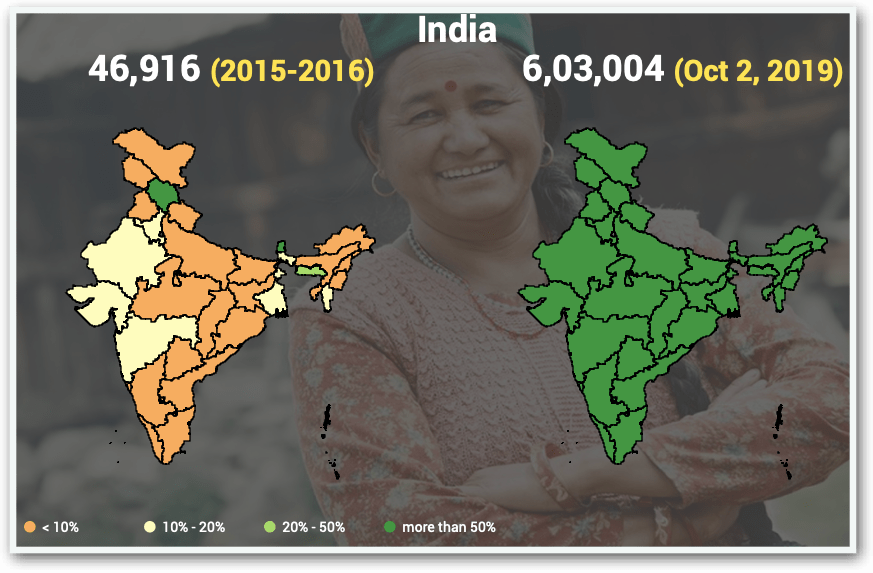

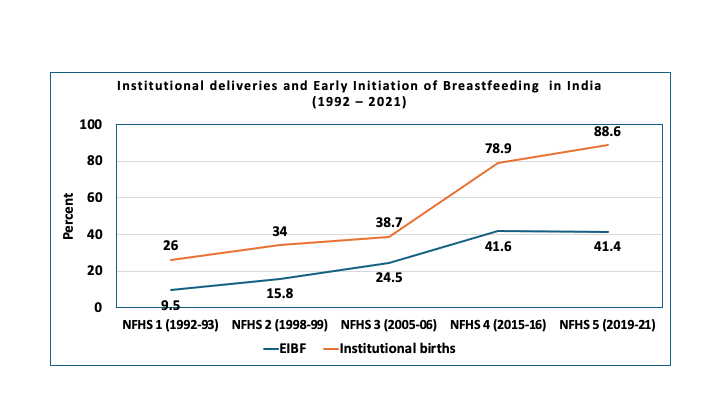

Early Initiation of Breastfeeding (EIB) is practiced in only 41.4% of births in India, meaning that every second newborn misses out on its proven, life-saving benefits. Alarmingly, India’s rate of EIB is lower than the global average of 48%.

With nearly 25 million births every year, a vast majority (88.6%) take place in health facilities — 61.9% in public institutions and 26.2% in private ones. Despite this, more than half of these facility-born infants are not breastfed within the first hour of birth. In absolute terms, of the 2.5 crore annual deliveries, only about 1 crore mothers (41.6%) initiate breastfeeding early. More worrisome is the fact that since last so many years, there is no change in the situation. This highlights a serious gap in breastfeeding support and counseling within both public and private healthcare systems, raising urgent concerns about the quality of maternal and newborn care practices across the country.

What are the barriers to the early initiation of breastfeeding in India?

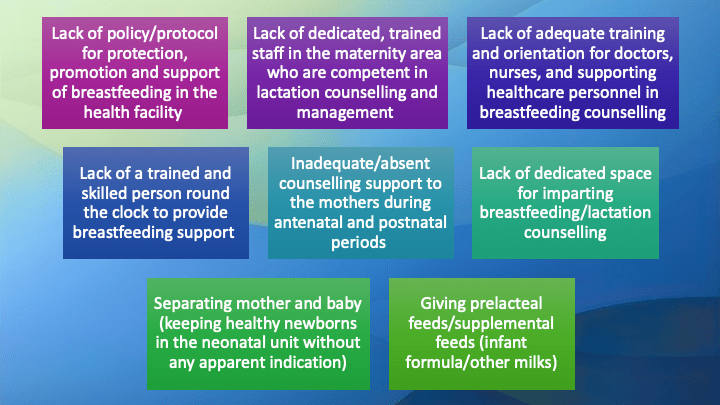

Breastfeeding unfriendly hospital practices

Undesirable practices in the health facilities undermines establishment of lactation and hinders the mother to practice optimal breastfeeding including Early Initiation of Breastfeeding. This has been documented in several published studies from India (See study 1; study 2; study 3; study 4; study 5). Heavy workload on the existing staff – Doctors and nurses are already carrying heavy responsibilities, leaving them with limited time to engage in counselling or extend skilled support to mothers.

Some of the breastfeeding unfriendly hospitals practices identified in the above-mentioned studies are listed below.

Many hospitals are not practicing globally recommended, evidence based breastfeeding friendly practices in the delivery room like skin-to-skin care after birth, latch-on in the delivery room/operation theatre, assigning dedicated staff for early latch-on and documenting early latch-on in the baby records.

In many hospitals, existing staff including doctors and nurses are already having heavy workload and do not find dedicated time to counsel and provide skilled support to the mothers.

Inadequate protection of breastfeeding from commercial interests: Baby food companies circumvent ethical and legal guidelines by directly targeting mothers—often presenting themselves as providers of childcare or breastfeeding education. They further promote their brands by displaying products within health facilities and promoting their image through sponsorships, gifts, and academic event funding, undermining unbiased breastfeeding support.

Sub-optimal Maternal Awareness and Knowledge

Many mothers, particularly first-time mothers (primigravida), have limited awareness about the importance of initiating breastfeeding early. This gap often arises from inadequate information provided during antenatal visits and insufficient emphasis on breastfeeding counselling. As a result, when asked to begin breastfeeding immediately after birth, many mothers feel unprepared. Influenced by their own uncertainty and by family members who share common myths—such as the belief that breastmilk is insufficient during the initial days—they may turn to infant formula instead of exclusive breastfeeding.

Harmful Cultural Practices and Beliefs

In many parts of India, cultural norms and traditional practices continue to encourage behaviors such as pre-lacteal feeding (administration of honey, water, or other substances before initiating breastfeeding) and the discarding of colostrum. These practices, though deeply rooted in custom, contribute to suboptimal newborn nutrition and expose infants to health risks, underscoring the need for sustained awareness and behavior change interventions.

Caesarean Section (CS) Deliveries

Caesarean section is associated with delayed initiation of breastfeeding, which can negatively affect newborn health outcomes. In India, about 21.5% of all births are delivered by caesarean section—47.4% in private facilities and 14.3% in public (government) facilities. This means that roughly one in every five babies in India is now born through a C-section, and the trend has been steadily rising over the years. Importantly, in most CS deliveries where the newborn is stable, breastfeeding can and should be initiated in the operation room itself to support optimal early bonding and nutrition.

However, initiation of breastfeeding is delayed in CS deliveries due to several reasons.

- There is a common misconception within communities that mothers who deliver by caesarean section (CS) produce less breastmilk and therefore cannot breastfeed adequately. In reality, this belief is not supported by scientific evidence. The physiological mechanisms that regulate breastmilk production and supply function in the same way, regardless of whether the birth is vaginal or by caesarean section.

- A post‑caesarean mother often requires additional support to initiate breastfeeding, particularly within the first 24 hours when she may be confined to a supine position. In the absence of appropriate assistance for positioning and latching, there is an increased likelihood of early introduction of infant formula.

- Following a cesarean delivery, there is often a delay in transferring the mother from the post-operative care unit to the postnatal ward. During this period, even clinically stable newborns are routinely separated from their mothers and admitted to the NICU for observation, where they may be unnecessarily exposed to formula feeding.

With timely support, guidance, and encouragement, mothers who undergo CS can successfully initiate and sustain breastfeeding. Help from a trained and skilled person is required for the mother to breastfeed the baby.

Inadequate Support from Health Care Providers

A major barrier to the early initiation of breastfeeding is the limited support provided by maternal and child health care providers.

Several factors contribute to this challenge, including:

- A prevailing misconception among healthcare providers is that maternal milk production during the first few days postpartum is inadequate, which often leads to the recommendation or acceptance of formula feeding as a temporary substitute. This belief is particularly common following caesarean section (CS) deliveries, where breastfeeding is perceived to be more challenging. Correcting these misconceptions through evidence-based guidance is essential to ensure that mothers receive appropriate support for early initiation and continued success of breastfeeding.

- Many healthcare providers lack adequate knowledge and practical skills to support mothers in achieving effective latching or to offer evidence-based counselling on infant feeding. This gap largely stems from limited breastfeeding education during undergraduate and postgraduate training. Consequently, when confronted with feeding-related concerns from mothers and families, providers may often default to the easier option of recommending formula feeding.

- Baby food companies often target healthcare professionals with commercially driven and scientifically biased information, aiming to influence their recommendations and encourage the use of infant formula.

Facilitating Early Initiation of Breastfeeding: What Needs to be Done at health care facilities

In most cases, breastfeeding can be initiated within the first hour after birth with appropriate support from trained healthcare staff and family members (See here). Achieving this goal requires coordinated action at multiple levels, including national and state policies as well as programmatic interventions. This write-up, however, focuses on the steps that can be undertaken at individual healthcare facilities. The following section outlines key interventions needed in hospitals and maternity centers, where the majority of deliveries take place.

Learning and unlearning among the health care providers about the breastfeeding:

All the professionals providing maternal and child health care in the hospital should be sensitized about the importance of breastfeeding for the baby, mother, hospital staff and the hospital. This should include health care providers working in the pediatrics, obstetrics, delivery room, operation theatre, out-patient department, post-natal ward. All the consultants, resident doctors, interns, post-graduate students, nursing staff, and the general duty attendants working in the above areas should be included in the sensitization programme. The idea is that everyone caring the mother, baby and the family should speak in similar voice. They should be apprised about the health and nutrition benefits of successful breastfeeding to the mother- baby dyad; benefit to the hospital staff in terms of decreased morbidities in the baby leading to decreased workload; benefit to the hospital in terms of improving the quality of care to the mother and the baby. They should learn that infant formula is not a safe alternative to breastfeeding.

Health facility should establish optimal breastfeeding services:

The need is to implement a structured programmes in the health facilities to improve breastfeeding initiation, duration of any breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding. This is possible to achieve, as concluded in a systematic review. Hospital practices can be improved if the health facilities address the identified barriers and show determination and desire to act.

Following actions are important for strengthening Hospital Breastfeeding Services

- Hospital administration recognizing the breastfeeding services as an important component of obstetrics and childcare services. They should take necessary steps for improving hospital practices to ensure successful breastfeeding by the mothers.

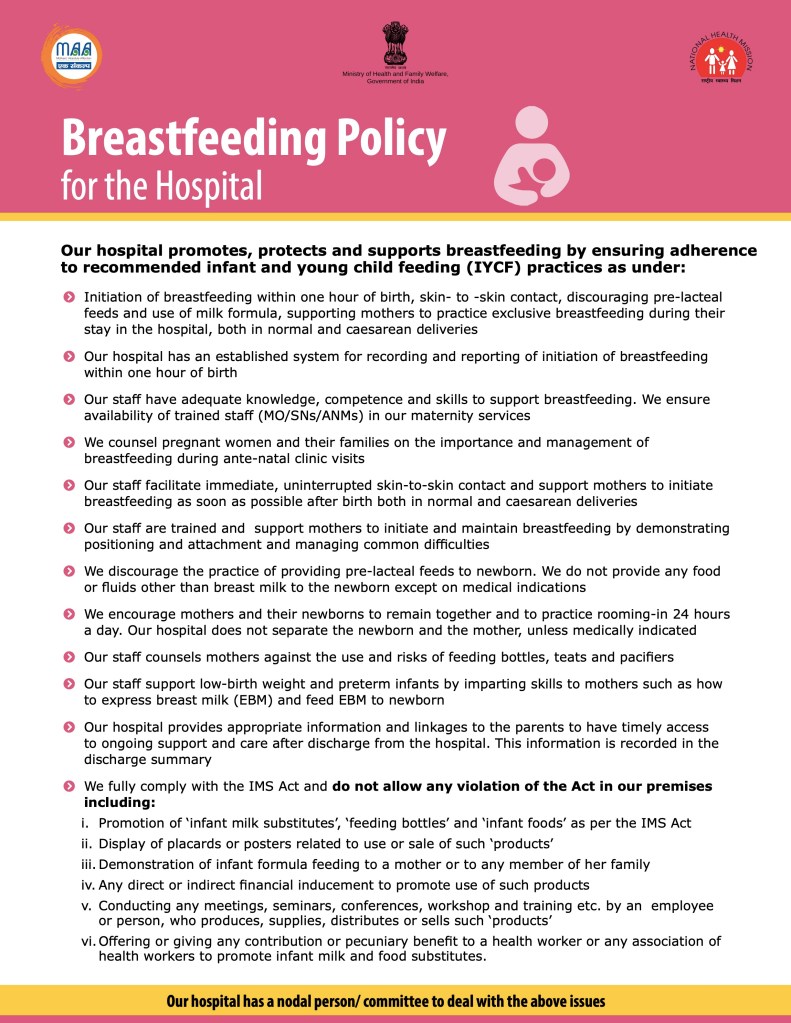

- Developing and adopting a breastfeeding policy for the hospital. MOHFW, Government of India has developed a prototype breastfeeding policy for hospitals, which can be adopted by the hospitals. (See the image at the end of the article)

- Employing trained lactation support professionals

- Organizing trainings of health care providers on breastfeeding counselling

- Establishing ante-natal breastfeeding counselling service in the hospital

- Establishing breastfeeding corners/room in the hospital premises

- Maintaining and reporting breastfeeding data regularly

- Auditing cesarean deliveries regularly and having a policy to use this method of delivery only for the established clinical indications

- Prohibiting promotion of baby foods and feeding bottles in the hospital

- Going for accreditation of the hospital for BFHI as a quality assurance programme

- Adopting Quality Improvement Methods. ( See here)

These steps, if adopted collectively, can foster a supportive environment for breastfeeding, benefiting mothers and infants, and aligning the hospital with national and global standards of obstetric and childcare excellence.

Epilogue

The discussion above highlights that early initiation of breastfeeding is crucial for the optimal growth and development of infants, as well as for the health and well-being of mothers. Strengthening early initiation practices is both necessary and achievable through focused attention and structured interventions at health facilities, within communities, and by government agencies. Health professionals, in particular, should play a central role in guiding and supporting mothers to begin breastfeeding within the first hour of birth.